By Celia Shortt

In Guyana

Cultures all over the world have one thing in common, death. It might seem kind of morbid to be talking about death, but discovering this commonality taught me a valuable truth about what people all over the world share.

Recently, a friend and coworker of mine lost someone in her family. The day it happened, we were busy making plans for the evening and looking forward to the weekend when her phone rang. It’s always like that, no matter where you are. You’re going about your business, living your life when the hammer falls and life is suddenly never the same. I mean, we were on our way out the door, getting ready to call the taxi when she got that phone call saying that something was wrong. She received the final word that he had passed away when we were in the car on the way to her house.

In less than 20 minutes, normal life had been shattered. Our evening and weekend plans were no longer on our minds. Instead, my friend was sitting there in shock, and I was praying that everything would be okay.

In does not matter what continent you’re on or from, death affects all of us the same way. Its sudden and unannounced presence hits all of our lives and changes them forever. No person on Earth can escape any of that. We will all face it, and we will all be hurt by it.

I wish I could say that this story had a happy ending. I visited my friend’s family about a week after the death occurred. They are all hurting, but they are surviving. They are moving on from what happened and are trying to heal. Like at home, I feel useless with this type of situation. I never really know what to say or do. Even in this country, just like at home, that does not matter. All I can do is be there and support them.

I am farther away from any familiarity than I have ever been, but the longer I am here, the more I realize that there are fundamental aspects of life that every culture and country faces. I think we all have more in common than we realize.

Friday, December 11, 2009

Diary from Guyana – What We Have in Common

Monday, November 30, 2009

Remembering, or forgettting, Yitzhak Rabin

By Michael Barajas

Commemorating the assassination the late Israeli Prime Minister Yitzhak Rabin has raised controversy ever since an extremist right-wing Orthodox Jewish man shot him dead 14 years ago.

Rabin signed the Oslo Accords in 1993, officially recognizing the P.L.O. and creating the Palestinian Authority while for the first time also making partial land concessions to the Palestinians. The landmark agreement also brought Israel and the Palestinians to the negotiating table for the first time, ending much of the violence of the First Intifada, or Palestinian uprising.

But ever since Rabin and Yasser Arafat signed the Oslo Accords, Israelis have remained divided over what exactly the agreement accomplished. Many on the left cheer Rabin, praising him for pushing peace forward, while many on the right – and Orthodox religious communities – demonize him for giving up Israeli land and recognizing any Palestinian leadership.

In recent years, a new phenomenon has popped up in Israel in which Israeli rightists and Orthodox religious communities focus solely on commemorating the death of the Jewish matriarch Rachel at Rachel’s Tomb, disregarding the Rabin celebrations. Some say it’s a way to effectively dodge the dicey political issue that Rabin’s death evokes, turning the yearly gathering at Rachel’s tomb into a counter-Rabin celebration.

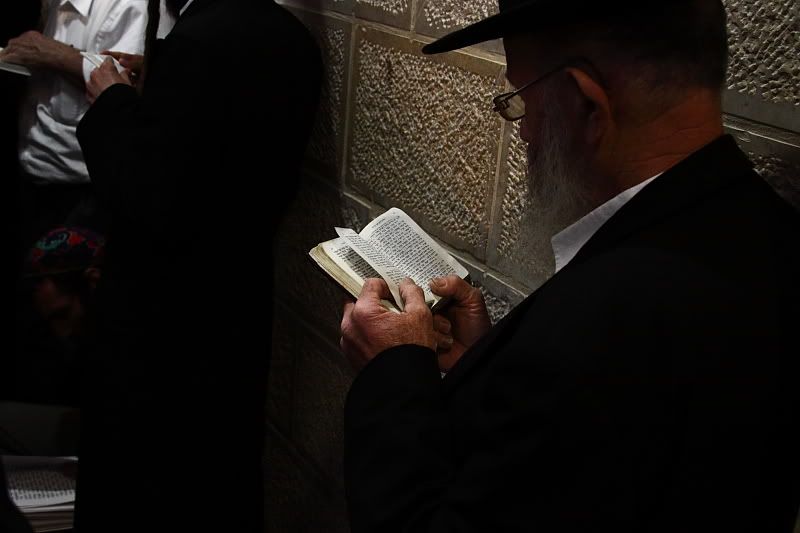

An Orthodox religious man prays inside Rachel's Tomb

Efrat Zemer wrote this week in the Israeli tabloid Maariv that many state religious schools have even begun focusing solely on the Jewish matriarch, though commemoration of Rabin in Israeli schools is mandatory. The anniversary of Rachel’s death, he writes, has suddenly become more prominent than it was in the past, before Rabin’s assassination.

It shows, Zemer says, how this divided nation is dealing with its troubled past. He claims many in the religious community separate themselves from the Rabin memorial, saying they don’t want to take part in remembering an assassination for which they were blamed. This year, organizers estimated that up to 150,000 people journeyed to Rachel’s tomb on the anniversary of both her and Rabin’s death – that’s up from 80,000 just last year.

The separation barrier surrounding the tomb complex

Though Rachel’s tomb is technically in the West Bank on the outskirts of Bethlehem, an Israeli barrier to separate it from the rest of the West Bank now surrounds it. The site is approachable from only from Israel, and access is generally restricted to tourists and Jewish pilgrims.

The area feels more like a heavily militarized zone than a tourist or pilgrimage site. The tomb is almost unrecognizable and blends in with the high walls, fences and razor wire surrounding it. The area was once a hotbed of violence during both Intifadas, and while some come here on the anniversary of Rachel’s death to escape the politically charged issue of Rabin’s murder, politics are hard to ignore while literally enclosed by the Israeli-West Bank separation wall.

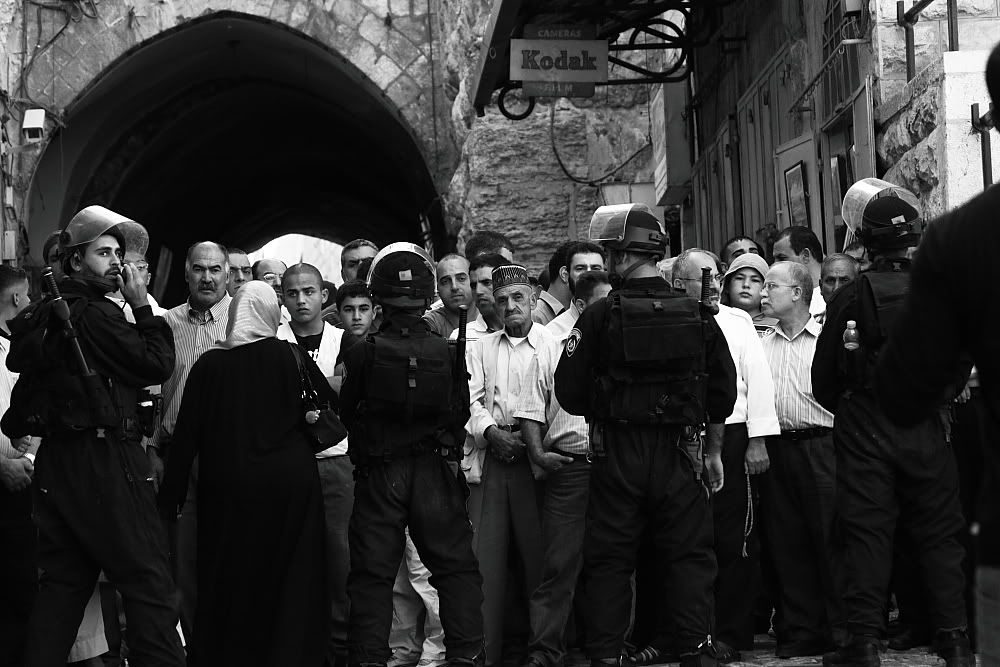

Israeli soldiers stand guard outside the tomb

When asked, one rabbi organizing busloads of religious men and women into the imposing tomb complex simply said, “Our focus is not on Rabin, it’s on Rachel. Yitzhak Rabin was also a child of God, you can pray for him too if you want.”

Some, even in government, have been more vocal about their opposition to Rabin’s remembrance. Israeli Cabinet member Michael Ben-Ari announced Thursday that he was boycotting a special cabinet session dedicated to the assassinated prime minister, saying it alienates the country’s right-wing and turns Oslo process into a “festival.” Thursday, right-wing Israeli activists passed out flyers at Israeli university campuses urging people to protest Rabin remembrance ceremonies taking place all over Israel this weekend.

Thursday, standing near the drab entrance to Rachel’s Tomb surrounded by religious men bowing incessantly in prayer, one rabbi said, “Rabin was just a politician. People won’t remember him in 100 years from now. We’ll always remember Rachel.”

A guard outside Rachel's tomb

Michael Barajas is a recent Scripps graduate. He is currently interning with the Associated Press in Jerusalem, Israel. To visit his portfolio website, go to: http://michaelsbarajas.com

Images and content copyright Michael Barajas

Topics: Israel

Diary from Guyana - WORSHIPING IN "A FOREIGN LAND"

By Celia Shortt

By Celia Shortt

Church is an important part of my life wherever I am. So, when I moved to Guyana, it was a natural thing for me to look for a church here.

Now, I go to church for many reasons. One of the most important reasons is that I enjoy the fellowship and encouragement I receive when I am with other believers. Well, like a lot here, church is much different than church back home.

First off, like most places here, I can’t blend in. I stand out everywhere I go. That makes it hard when I want to just sit back and absorb what the pastor is saying. Second, it also makes it hard to worship when everything around me is different. I can’t revel in the comfort of what I am used to.

So, I grew discouraged with church. In fact, I even thought about not going one Sunday morning. For me, that was breaking a lifelong habit. I wasn’t ready to do that, so I went to church, reluctantly.

When I arrived, I had to look around to make sure I was in the right place. There was an entire group of Americans there. I was a bit overwhelmed, so I did my usual act and sat at the end of one of the back pews. I wasn’t fast enough. The Americans started talking to me while another quickly snapped my picture with one of the children at church.

These folks were from a church in the U.S. and were visiting to do some missions work with the children’s home that was run by the church. Not only that, but their team leader lived in Guyana and was going to be back here permanently in January. In less than five minutes, God had made my trips to church worth everything that it took to get me there.

Despite the differences between my church here and my church back home, I still see God working in both places. That is one thing that hasn’t changed with my location.

Sunday, November 15, 2009

Diary from Guyana – PERSEVERANCE

By Celia Shortt

It took a week for IT to hit me. IT was homesickness. I realized one afternoon that I wanted to go home. My life, my family, and friends were on another continent (which might as well have been another planet), and I was here, alone, in Guyana.

I tried to keep myself busy by sightseeing, but as I observed the view from the top of the highest single drop waterfall in the world, all I could think about was how much my family would enjoy it. I went to my apartment and cried. I still had 10 months and three weeks to go. I knew how much my eyes and head would hurt and how red and raw my face would be if I cried every day.

This place was so much different than home. First, this place was hot, and there was little to no air conditioning. Second, the fast internet here is slower than the slow internet at home. It takes at least one day to download an episode of any television show from iTunes. So one day to download a show that takes 45 minutes to watch. Third, it is impossible for me to blend in here. I’m pretty much the only white person wherever I go. When I teach, I’m either the only white person or one of two white people. More than that, my accent is so completely different than the ones here that even on the phone I can’t blend in.

Ten months and three weeks of this might as well have been the rest of my life. I spent countless hours on the phone with my mom trying to figure out how to deal with this. The theme in everything she told me was to persevere. Easier said than done, but to honor my mother, I persevered at perseverance.

I now have about seven months and two and a half weeks left here. I still miss my family, friends, and life in the U.S. Guyana is still hot with very little air conditioning. It still takes at least a day to download one episode of anything, and I can only blend in when I’m with folks from the U.S. Embassy. Through it all, I persevere, knowing that my perseverance will allow me to learn lessons impossible any other way. I’m positive, too, that with my perseverance will come some great experiences that will make my life richer than it would have been without.

Saturday, November 14, 2009

Expelled West Bank student petitions Israel court

By MICHAEL BARAJAS

The Associated Press

Thursday, November 12, 2009

JERUSALEM — A female Palestinian student who says she was handcuffed, blindfolded and hauled off to the Gaza Strip by the Israeli army in the middle of the night late last month asked Israel's supreme court Thursday to let her return to her studies in the West Bank.

The incident highlights a deep fear among the thousands of Palestinians originally from Gaza who now live in the West Bank — sudden expulsion by the Israelis to the Hamas-ruled coastal strip.

Berlanty Azzam, 21, was only two months away from finishing her business degree at Bethlehem University when she was stopped by Israeli soldiers at a checkpoint in the West Bank. After noticing her Gaza-issued identity card, soldiers detained Azzam and put her in the back of an army jeep.

When Israeli soldiers led her out of the vehicle around midnight, Azzam was shocked to see where she was — the border between Gaza and Israel.

"I was so surprised, I didn't know what to say," Azzam recalled. "I tried to ask the soldiers if there's any other solution than this, and they just said, 'No, you've reached Gaza, you have to enter.'"

Yadin Elam, a lawyer with the Israeli human rights group Gisha representing Azzam, said such incidents happen on a daily basis and constitute a removal "by force" on the part of Israel of Palestinians from West Bank to Gaza.

Elam estimated that there are currently as many as 25,000 Palestinians living in the West Bank in danger of being deported to Gaza because their identification cards list a Gaza address.

Rights group lawyers and university faculty members asked the supreme court Thursday to allow Azzam to return to the West Bank. Azzam, denied a permit to travel to Jerusalem for the day, remains in Gaza.

Elam said during the hearing that Israel violated Azzam's basic legal rights by denying her access to a lawyer before deportation.

The Israeli supreme court ruled in 2007 that Gaza students had to obtain a permit if they wished to study in the West Bank. Elam said such permits did not exist when Azzam enrolled in Bethlehem University in 2005. At the time, she obtained a four-day permit to enter Israel so she could cross over to the West Bank.

"How could they deport her for not having a permit that didn't even exist?" Elam said.

The West Bank and Gaza Strip lie on opposite sides of Israel. The Palestinians hope to form an independent state that includes both territories. Under the 1993 Oslo interim peace accord, both areas were to be considered a single territorial unit. But since Hamas militants violently seized control of Gaza in 2007, Israel has branded Gaza an enemy entity and imposed a blockade that includes strict travel restrictions on residents.

The Israeli army says Azzam was living in the West Bank illegally, and was rightly returned to Gaza.

The court on Thursday remanded the case to a military hearing to be held at the Gaza border next week, where Azzam can attend.

"My priority, what's most important, is to get back to my studies," Azzam said, speaking by phone from Gaza. "I was so close to finishing, I just want to get back to Bethlehem and finish."

Copyright © 2009 The Associated Press. All rights reserved.

Michael Barajas is a recent Scripps graduate. He is currently interning with the Associated Press in Jerusalem, Israel. To visit his portfolio website, go to: www.michaelsbarajas.com

Thursday, November 5, 2009

Israel seizes massive weapons shipment

By Michael Barajas

Wednesday the Israeli navy seized a ship carrying an enormous illegal weapons cache off the coast of Cyprus. The Israelis claim they have shipping documents showing the weapons were sent from Iran to arm the Islamic militant group Hezbollah in the south of Lebanon.

I was lucky enought to spend most of the day reporting from the southern Israeli port of Ashdod, where the army brought the ship. The military walk me around the nearby dock where they had lined up row after row of shipping containers, their contents spilling out onto the pavement revealing the hundreds boxes of rockets, grenades and other munitions. The stash contained hundreds of the same type of the rockets Hamas and Hezbollah have used to attack Israel in the past.

The Israelis are calling this the smoking gun that proves Iran's determination to arm militant groups that continue to threaten the Jewish state - Hezbollah in Lebanon and Hamas in the Gaza Strip.

All of this comes at a time when Israel is under fire for its conduct in last year's harsh Gaza offensive, with a U.N. report accusing the country of war crimes for deliberately targeting Palestinian civilians. Israel says the report's claims are outrageous and that it debases Israel's right to self-defense.

Israeli politicians and experts explained to me today that Israel is sure to use this incident for its benefit, shifting the focus to Iran - to which Israel insists the international community needs to take a more hard-line stance - and drawing attention away from the damning U.N. report.

Showing that it plans to fully publicize the incident, Israel has already invited swaths of foreign ambassadors to tour the weapons stockpile, which is both stunning and unsettling to see first-hand.

Read the story here.

Michael Barajas is a recent Scripps graduate. He is currently interning with the Associated Press in Jerusalem, Israel. To visit his portfolio website, go to: www.michaelsbarajas.com

Images and content copyright Michael Barajas

Topics: Israel

Tuesday, November 3, 2009

Jewish settlers evict Arab east Jerusalem family

By MICHAEL BARAJAS

The Associated Press

Tuesday, November 3, 2009

JERUSALEM -- Jewish settlers forced their way into a disputed house in east Jerusalem on Tuesday, using hired guards to evict an elderly Palestinian woman and tossing the other residents' belongings into the rain-swept yard.

The settlers displayed what they said was a court order granting them ownership of the simple one-story building. Human rights groups said the takeover was a push by Jewish settlers to expand their presence in east Jerusalem.

Sovereignty over the traditionally Arab sector is one of the most explosive issues in the Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

Israel captured the area in the 1967 Mideast war and immediately annexed it - a move recognized by no other country. The Palestinians consider east Jerusalem the capital of their hoped-for state.

Palestinians and their Israeli supporters clashed with the Jewish settlers after they took over the building, and police intervened to restore calm, arresting one of the Israeli protesters, a police spokesman said.

Similar clashes have broken out over nearby buildings in recent months.

"It's clear to me that this is another case of settlers taking the law into their own hands," said Rabbi Yehiel Grenimann of Rabbis for Human Rights, an Israeli group that opposes Palestinian home evictions and demolitions.

"It's just another step-by-step way of pushing them (the Palestinians) out," he said.

Grenimann said 29 members of the al-Kurd family lived in the house evicted on Tuesday. Some of them had settled there after they were evicted from another house in the same neighborhood, following the Israeli Supreme Court's decision to uphold the settlers' claim to the ownership of that building.

Conflicting claims and religious tensions make east Jerusalem - which includes the Old City, with key holy sites revered by Muslims, Jews and Christians - a frequent flashpoint.

Palestinians want to make it their future capital, while Israel insists on retaining control of the whole city.

Israel has built homes for more than 180,000 Jews in new east Jerusalem neighborhoods since the 1967 annexation.

The U.S. and others have criticized Israeli settlement in east Jerusalem and urged Israel to stop evicting Palestinians and demolishing their homes there, saying such moves disrupt peace efforts.

http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2009/11/03/AR2009110301705.html

© 2009 The Associated Press

Michael Barajas is a recent Scripps graduate. He is currently interning with the Associated Press in Jerusalem, Israel. To visit his portfolio website, go to: www.michaelsbarajas.comTopics: Israeli settlers

Thursday, October 29, 2009

West Bank

By Michael Barajas

Local Palestinians and international activists have protested the Israel-West Bank separation barrier in the West Bank villages of Bil'in and Ni'lin for almost five years. The barrier cuts into significant portions of the villagers' farm land. Israeli soldiers typically fire tear gas and rubber bullets at protesters, who gather weekly.

Protesters meet in Bil'in's village center and march down to a ravine near the barrier.

A Palestinian teenager in Bil'in covering his face after running through a cloud of tear gas.

A Palestinian boy hurls a tear-gas grenade back at Israeli soldiers in Bil'in

A Palestinian protester in the West Bank village of Ni'in

Michael Barajas is a recent Scripps graduate. He is currently interning with the Associated Press in Jerusalem, Israel. To visit his portfolio website, go to: www.michaelsbarajas.com

Images and content copyright Michael Barajas

Topics: West Bank

Old City, New Violence

By Michael Barajas

Violence erupted once again in Jerusalem's Old City on Sunday as Israeli police stormed the Temple Mount to chase off violent Palestinian protesters. This is the second time this month that Israel has dispatched a heavy police force to quell violence in the Old City, heightening tensions all over Jerusalem.

This latest outburst seemed to be set off by a swath of rumors started by Muslim leaders in the north and East Jerusalem - that extremist Jewish groups were planning on taking over the Temple Mount (what Muslims refer to as "The Noble Sanctuary" which houses the Dome of the Rock and the Al-Aqsa mosque). Of course, nothing supports those claims.

Masked Palestinian protesters began gathering on the Temple Mount early Sunday morning, claiming they were "defending Al-Aqsa" against invading Jewish forces. Eventually they began throwing rocks and petrol bombs at Israeli police. By the end of the day, 18 Palestinians were arrested, 25 were injured, and hundreds remained holed up inside the Al-Aqsa mosque.

The Temple Mount is one of the holiest sites for both Jews and Muslims. In the past, clashes in and near the Old City have sparked serious, prolonged violence. Click here to read the AP story about this most recent round of clashes.

I showed up to report from the Old City between waves of violence that morning - the more serious clashes seemed to go off around 9 am and 10:30 am.

Right after entering through Lions' Gate, which leads straight into the Muslim Quarter and the ramp up to Al-Aqsa, I saw Israeli police set up a barrier behind me. Within minutes, I saw Palestinian men and women lining up, trying to enter the Old City for midday prayers to no avail.

To one side, Israeli police donning helmets and Plexiglas shields set up a barrier in front of the entrance to the Temple Mount. Palestinian women were screaming, crying and begging to be let in. I heard one yelling that her son was inside - she said he was young and probably scared.

At the same moment, rocks and glass bottles rained down on Israeli Police yards away as young Palestinian boys darted in and out of alleyways throwing whatever they could. One boy ducked behind a shopping cart filled with rubble, occasionally standing up to launch stones as big as his fist. Police fired stun-grenades down the small alleys trying to disperse the protesters. A local Palestinian woman told me, "This is what happens when peace-talks end."

By this time, more and more older Palestinian men and women had gathered in the street, trying to get to Al-Aqsa. Somewhat arbitrarily, Israeli police would get behind them and form a line, pushing them forward through the gate. It was difficult not to get caught in the middle.

Just before noon, the group of Palestinian men that remained near the Al-Aqsa ramp began to form two lines. I immediately knew what they were doing. The men closed their eyes and began to pray, while Israeli police stood behind their shields chatting and occasionally taking drags off their cigarettes. Shock-grenades continued to ring out through the streets.

Michael Barajas is a recent Scripps graduate. He is currently interning with the Associated Press in Jerusalem, Israel. To visit his portfolio website, go to: www.michaelsbarajas.com

Images and content copyright Michael Barajas

Topics: Jerusalem

Monday, October 26, 2009

IIJ HOSTS INTERNATIONAL JOURNALIST & FILMMAKER

The Institute for International Journalism and the College of Communication in conjunction with The Pulitzer Center on Crisis Reporting has organized yet another campus visit by independent filmmaker and roving journalist, Steve Sapienza. Steve will be here from Tuesday October 27 to Thursday October 29, 2009.

He will share his experiences in reporting international crises. He will give lectures on Tuesday and Wednesday, which will provide Ohio University students with fresh information on global issues such as water crisis and the climate change in countries he has covered.

“Easy Like Water: Reporting from the Front Line of Climate Change”

In Bangladesh, water poses a relentless threat to about 150 million people in a country the size of Iowa. With increasingly violent cyclones and accelerating glacier melt upstream, flooding may create more than 20 million “climate refugees” from Bangladesh, alone, by 2030. India is already building walls to keep Bangladeshis out.

Steve will speak to the university community in Anderson Auditorium located in Scripps Hall, Room 111 on October 28, at 6pm. Come and join the conversation on global climate change in this region with Steve Sapienza, an award-winning news and documentary producer who has covered a wide range of global issues on Wednesday October 28, 2009 from 6pm to 7pm in Anderson Auditorium.

Stephen Sapienza is an award-winning news and documentary producer who has covered a wide range of global issues, including the HIV crisis in

He will dine with faculty and students, and also hold one-on-one talks with a few students in Scripps 205 and in Sing Tao 101. Please contact Professor Kalyango if you are interested in having an exclusive visit with Steve on Thursday morning between 10:00 am and 11:30am.

Friday, October 23, 2009

Television in Guyana – Lack of Identity Expressed through Media

By Celia Shortt

As a journalist, one of the big things I look at when I engage with another culture is their media system. So much can be learned about a culture and its identity from their media. An observer can see their pride in their country, their struggles as a nation, or their desire for change. When I arrived in Georgetown, Guyana, I was anxious to view the country through its media and learn as much as possible about it.

So far, in my short time here, the biggest thing I have learned about Guyana from their media is that they are in search of their identity as media. Most of their programming is taken from American networks and programming. When I say taken, I don’t mean conceptualized or based on, I mean directly taken. They take blocks of programming from an American television station, commercials and all, and air it as their own on television stations. They do insert some of their own commercials over the American ones, but it’s still predominantly American programming. The majority of their news is even American. Like the other programming, they borrow, television stations here take blocks of programming from American cable news networks and air it for some of their evening newscasts.

For me, an American living in Guyana, the large amount of American programming is quite nice. When I came here, it did cross my mind that I would miss certain television shows. Not to mention, American news. So far, I have been able to follow both because of their dependence on American programming.

Now, some stations do have some local programming and local newscasts, but what little there is was created by people who have not had proper training. What television and/or media training they’ve received they’ve picked up along the way by others who may or may not have had proper training.

Despite these issues, I still learned quite a bit about Guyana. First, in the small amount of original programming, I could see the pride the Guyanese have in their country. Their morning news shows contain programming that shows what their country has to offer its citizens and its visitors, as well as the natural beauty their countrys possesses. The expression of this pride, however, is curtailed due to their lack of training. In other words, their lack of training makes it hard for them to professionally express their pride in their country through their media.

This lack of media training is perhaps the biggest thing I learned about the Guyanese culture. It has led to a struggle for them to express their identity and it has caused a desire for change so that they can do their job well.

In the first month that I was here, I was part of a television workshop which had a goal of training Guyanese journalists so that they could do their jobs better. Most who came did not know how to properly construct a news story. In addition, most did not know how to correctly navigate around the journalistic restrictions in the country. They were doing the best that they could with what they had. Seeing these journalists learn some of the necessary skills to be an effective journalist was not half as exciting as seeing them cultivate the desire to become a driving force in Guyana and the rest of the world.

In the time since the workshop, I have already seen some changes in the news programming. The stories are written and filmed better than before. Additionally, behind the scenes, journalists are implementing changes to help them do their jobs well.

As an observer, it is exciting for me to see people learn new things. As a journalist, however, it’s exciting for me to see Guyana discover Guyanese journalism instead of simply having journalism in Guyana.

Diary from Guyana - Embracing a New Culture

By Celia Shortt

The day I arrived in Guyana, I remembered that from the airplane, the dense jungle looked like broccoli. I also remembered seeing a tiny number of buildings that were scattered among those trees. This picture grew larger as the airplane continued its descent onto the runway. When we landed, I took a deep breath and reconciled to myself that I had just reached my home for the next 11 months, Georgetown, Guyana.

Before coming to Guyana, I had traveled internationally. I had not, however, lived in a different culture for this long of an amount of a time. I naively assumed that I would pick up and adapt to this new place and new culture quickly and flawlessly. It took no time at all for me to realize that wouldn’t necessarily be the case.

The first lesson I learned was that when embracing or engaging in a new culture, it is important to remember that what you are used to in your culture probably means something completely different where you are.

In America, when one sees a large tortilla, meat, beans, and rice, one word pops into his or her mind, burrito! It makes perfect sense, the meat, the beans, and rice go into the tortilla. The tortilla is then rolled up into a cylinder like shape and either eaten with one’s hands or a knife and fork. In Guyana, however, those four elements mean something completely different.

About a month after I arrived in Guyana, my coworker and I stopped at her house so we could carpool to an event we had that evening. When we arrived, her mother in law had a snack waiting for us. On the kitchen table were tortillas, meat, beans, and rice. Now, my friend told me this was Roti, but my brain told me this was a burrito. Being in a new country, I did not want to assume that was how to eat it, so I watched my friend prepare hers. Sure enough, she began to put the beans and meat into the tortilla. I went ahead and followed suit. I put everything, rice included, in the tortilla, wrapped it up and started eating it with a knife and fork.

I was several bites in before I realized both my friend and her mother in law were staring at me.

“What are you doing?” she asked.

“I’m eating Roti,” I said.

“Why are you eating it like that, and why did you put the rice inside it?” she asked while at the same time trying not to laugh.

“Where else was I supposed to put it?” I asked with a confused and baffled look on my face.

After a pause, we both looked at each other and started to laugh. Apparently here, the rice is always on the side. That night after laughing a lot at myself and watching my coworker and her mother in law laugh at my roti, I realized that my faux paus could be applied to a larger lesson. When you embrace a new culture, you probably won’t get it right the first time. However, if you learn to laugh at yourself and keep trying, you will gain new friends, new life, and wonderfully new and memorable experiences.

Tuesday, July 21, 2009

IIIJ FACILITATES E. SCHNIER’S REPORTING ENTERPRISE IN SOUTH AFRICA

"The scholarship funds given to Ellen are sufficient to cover her return air fare to South Africa, costs for ground transportation to go to work while in Johannesburg, and lodging for the three months," said Professor Yusuf Kalyango, Director of the Institute. Ellen joins an exclusive fraternity of more than 200 journalism majors who have received international journalism scholarships through the IIJ to intern in more than 30 countries around the world. Other recipients of this year’s international scholarships include Michael Barajas who will travel to Jerusalem in Israel to intern with the Associated Press and Stine Eckert who will intern with the Aljazeera network in Washington, D.C.

While in South Africa, Ellen hopes to learn about the international news environment in one of the largest news markets in the world. It will be a combination of an advanced, well-developed news organization in an industrialized city in the midst of Sub-Saharan Africa. The internship will give her an opportunity to experience South African life and culture. She hopes to investigate issues of poverty, race relations 15 years after the end of the apartheid, and health challenges the nation faces. “Hopefully, I will be able to travel to other African nations either with SABC or Channel Africa which is owned by SABC, to explore the culture and important issues in neighboring countries.

Ellen worked as a reporter and anchor on the Athens MidDay news, where she gathered news, wrote, and edited news packages for the television newscast. During an internship at WLWT, the NBC affiliate in Cincinnati, Ohio, she had the opportunity to conduct interviews, including one with the governor of Ohio. She competed on a nationally televised reality music competition, Clash of the Choirs, and her winning choir won $250,000 for Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. After the group was named Ambassadors of the Year in Cincinnati, she became a correspondent for WLWT Cincinnati’s local choir competition and produced profiles on several choirs for the evening news.

As for her graduate studies at Ohio University, Ellen has focused on African media and culture. Her thesis examined the U.S. network television coverage of events in Africa from 1977 to 2008. She also investigated and filed a special report for the IIJ’s Globetrotter Newsletter about Uganda’s successful campaign to reduce the infection rate of HIV/AIDS. A second special report investigated the Uganda Supreme Court’s decision to reinstate the use of the death penalty in Uganda.

Thursday, July 16, 2009

My orna and me -- Walking around as a woman in Dhaka, Bangladesh

Stine Eckert traveled to Bangladesh as a Pulitzer Center Student. Learn more and see all her reporting: http://www.

Whereas Western dress shirts and dress pants are the socially most acceptable outfit for Bangladeshi men, women predominantly still dress traditionally in Dhaka, Bangladesh. A note on experiencing clothing for women.

Every time I leave my room I have to wrap myself up, with a scarf called an orna.

My orna more or less lives on both of my shoulders and forms a “u” or “v”-shape in front of my breast to cover up my female shape. The ends of my orna dangle loosely on both sides of my back, reaching down to my hips or knees, depending on the length.

My orna has become my permanent companion in Bangladesh ever since a Bangladeshi girl showed me how to wear it properly. Well, at least I try. Without it, I have come to feel something is missing. This doesn’t mean we have a purely peaceful coexistence. No, my orna can be quite a nuisance and when I return to my room, I usually fling it on the sofa immediately. That’s in private.

In public, the orna (sometime also spelled urna) is part of the most prevalent outfit for women in Bangladesh, the so-called three-piece. It starts with baggy pants that taper down at the ankle of the foot and building a balloon shape around the woman’s thighs. They are matched by a long or short blouse and crowned by the orna.

For elements number one and two I stick to wearing jeans or loose linen pants I brought from home, matched by more or less bulky short-sleeve shirts, which seem to be accepted. Since element number three was missing, I was encouraged by several visitors to Bangladesh and Bangladeshis themselves, male and female, to fill the lack of element number three by draping some fabric around my upper body.

Embracing this new style of clothing, in the impossible attempt to blend into rest of female society, I donned a yellow-orange scarf, given to me by an Indian friend. I felt a bit like wearing the uniform of an alien species in Star Trek, a uniform I am constantly fighting with.

Every couple of minutes I need to reign in my orna to make sure it doesn’t travel down one of my shoulders. It also tries to move either to close to my neck softly strangling me when the dusty winds rush through the channel-like streets or droops to low uncovering the desired parts. Its fabric has an incessant desire to bond with the rough bark of trees, discover the pots of street vendors, flirt with the hood of cars that come dangerously close in the constantly thick traffic, or whisper to the concrete of the street.

Once a gusty wind blew the orna up into my face; girls driving by got a good laugh out of me. Imagine running an obstacle course while wearing a blanket in front of you.

I alternate between three ornas, a yellow-orange, a green, and a turquoise-brown one. One is like a short thin net, the other one like a thick blanket big enough to cover me for a nap, and the third feels like a long soft alga. All of them like to use my arms as slides, all of them are eager to make acquaintances with palm leaves along the road, all of them form alliances with my purse to keep me captive while I rummage for a handkerchief and try to keep breathing.

I have been trying to improve our relationship by observing how Bangladeshi women tame their ornas. They wear them elegantly with the color always matching the rest of their three-piece. Their ornas sit confidently on their shoulders, never misbehaving. If so, a tiny tuck shows them who’s the boss. Their ornas don’t seem to bother them. On the contrary, they employ it frequently to cover their heads against the hot-glowing sun. At least half the women don’t wear headscarves and the orna can be pulled over their heads quickly if needed such as when the muezzin calls for prayer and covering one’s head shows respect for the song-like reminder. But even then not all women seek cover.

In short, Bangladeshi women live in peace with their ornas, and the rest of their baggy dress. Few women wear jeans or other Western-style clothing. A 15-year old girl I interviewed at Nari Jibon, a small project teaching practical skills to women, told me she would like to wear jeans but it’s not accepted. In her tailoring class she learns how to sew fatuas—a shorter loose blouse—and three-pieces. That’s also what most shops offer in addition to the better-known saree, a five-meter long fabric matched by a tiny blouse, which seems to be worn more often by older women.

Traditional outfits for men consist of shirts and lungis, a skirt-like piece of fabric that is knotted around the hips and usually reaches to the ankles. But unlike the traditional dress of women, the lungi is not so prevalent among men, who can afford a business outfit. Workers on the street, rickshaw pullers, construction workers, street vendors all wear lungis. Businessmen who want respect don’t, at least not in public. I’ve been told they wear them at home and when they go to bed since they’re really comfortable.

Some other men on the streets wear long-sleeve shirts, called panjabi, matched by loose pants, and a little cap, often in white or lighter colors. Asking a Bangladeshi what that means it seemed that these men practice their religion more. Wearing a cap is a requirement for prayer, wearing the whole outfit might indicate that this man has completed his hajj, a pilgrimage to Mecca, which every Muslim should do once in her/his life.

The crisp business suits, tightly tailor fitted for the working male, however, rule the world of men in public while women walk wrapped in a cloud of pretty colored ornas and sarees.

Awkwardly I stumble along, ready to scold and adjust my orna for its next attempt to mock me.

Photo: Nipu, Shadia, and Tasnuva wear matching ornas -- big, long scarves -- to match the rest of their three-piece outfit, the traditional outfit for women in Bangladesh apart from the saree.

Learn more and see all of Stine's reporting: http://www.

The Other Side -- A Visist to Nari Jibon, a small women's aid project in Dhaka, Bangladesh

Stine Eckert traveled to Bangladesh as a Pulitzer Center Student. Learn more and see all her reporting: http://www.

Girls and women learn sowing, English and how to use a computer at Nari Jibon Development Foundation - A visit to a struggling women’s project in Dhaka. Part 3

“I want to get at least two or three computers hooked up to the Internet again,” says Golam Rabbany Sujan. He started as a resource officer at Nari Jibon in its beginning in 2005, later became project director.

The Internet was crucial for the Nari Jibon cyber café that gave women the chance to blog and write about their lives. He had to shut it down in February 2009. “Women don’t like to go to the cyber cafés outside because there are boys which make them feel uncomfortable,” Sujan explains the value of the café. And the women could apply their English and computer skills, too. “The students here were very proud to publish about their own interests,” he says.

But the 14,000 Tk ($205) per month to pay for the local Internet network were too much, Sujan says. He tries to keep up the Nari Jibon blog by posting occasionally from an outside cyber café.

His last post of June 23, 2009 tells the story of 13-year-old Rozina Akthar, who comes to Nari Jibon five times a week as she doesn’t go to school. As Rozina is deaf it was hard to communicate with her when I visited but she showed me her sowing. Sujan’s description on the blog of how Rozina recently got harassed on the street gives an example of the so-called eve-teasing, verbal insults that many Bangladeshi women experience but can do little about.

Mr. Sujan explains that at the moment the whole organization runs on about 14,000 Tk ($200) alone to pay electricity, the phone bill, some of the teachers and Ruma. Mr. Sujan himself and the English teacher work currently without pay.

The chance for more money only comes when Mr. Sujan can obtain a certificate to receive international donations. Since February 2009 Nari Jibon is registered as a Social Welfare Trust, a local Non-Governmental Organization (NGO). But that is not enough, Nari Jibon needs to obtain the sought-after NGO Bureau status to secure international donations. Yet, just getting the local NGO status was a year-long project.

“It took 36 documents to sign and $1,000 in lawyer fees to get the current status of Nari Jibon,” says Nari Jibon Assistant Director Katie Zaman, a master student in sociology at the University of Wisconsin-Madison who works on her thesis about women’s work and domestic violence in Bangladesh.

All the documents are ready to apply for the NGO Bureau status, says Mr. Sujan, but ironically more money is needed to get the certificates to tap international funds. It will need at least another 10,000 Tk ($150) in bribes, he says. “The more money we can give, the speedier will be the process.”

Former main donor and founder of Nari Jibon Dr. Kathryn B. Ward is tired and frustrated. She says she had to pull the plug at Nari Jibon in November 2008 after spending over $65,000 of her own money and more in research grants in the past four years to get the project established. She paid for computers, sewing equipment, and the office infrastructures; students always have paid a small fee to join classes and use the facilities. Some of them, however, expected Nari Jibon to come for free altogether.

Originally Dr. Ward had hoped that other NGOs would fund some of the redundant and less prepared staff and aides at Nari Jibon. As she works as a professor of sociology and women studies at Southern Illinois University, she says she cannot longer direct the project from overseas, nor afford the funding.

The “Mother of Nari Jibon,” as the caption of a photo in the Nari Jibon office affectionately calls her, had to let go of her project but her concern doesn’t end easily. Just recently she sent another $150, which came from her local food coop.

She says after repeatedly giving directions to and promises from the Nari Jibon in Dhaka, its staff needed to take more initiative on their funding, sustainability, and operations. “At the same time, Bangladesh authorities have made registration very difficult.” As a result, Nari Jibon has had difficulties in finding other donors without government registration, she says.

Frustration doesn’t stop with the money. Even though Nari Jibon lists the success stories of its students and the girls I met tell of their joy and pride to be able to have Nari Jibon to pursue their own interest, change in society comes slowly for women.

“The sex workers [who came to Nari Jibon] still have to go home at night and come back with bruises in the morning,” Dr. Ward says.

Currently, she says she needs a break from Nari Jibon and Bangladesh: ”You can have the best intentions and do good things but that doesn’t help with the system in the larger Bangladeshi society.”

Photos:

On the third floor of the apartment building in the area of Malibagh works the small organization Nari Jibon. Before they occupied several floors and can expand again when more money is available.

Dr. Kathryn B. Ward, professor of sociology and women studies at Southern Illinois University founded Nari Jibon. After giving more than $65,000 of her personal money, more in research grants, and time to establish the project she feels exhausted and frustrated.

Learn more and see all of Stine's reporting: http://www.

Wednesday, July 15, 2009

Ruma -- A Visit to Nari Jibon, a small women's aid project in Dhaka, Bangladesh

Stine Eckert traveled to Bangladesh as a Pulitzer Center Student. Learn more and see all her reporting: http://www.

Girls and women learn sewing, English, and how to use a computer at Nari Jibon Development Foundation -- A visit to a struggling women’s project in Dhaka. Part 2

As I talk with Nipu, Shadia, and Tasnuva, who learn English, sewing, and Microsoft Office at Nari Jibon, a quiet fragile women in a bright yellow sari drifts in and out of the doorframe of the computer room. Sixty-five-year old Ruma has been with Nari Jibon since the beginning of the project in March 2005. She helps the tailoring students, brings tea, and welcomes guests at Nari Jibon. She already greeted me as I only got half way up the stairs to the third floor where all classrooms and the office are located.

Ruma came to Dhaka 25 years ago, when she fled from her second husband in Khulna, a village in South West Bangladesh where he still works as a fisherman. As her first husband died she was forced to marry his younger brother, whom she didn’t like. In Dhaka she found work by ironing garments to support her two sons.

“Nari Jibon has changed my life positively,” she says. “If I had a chance like that earlier, I could have worked from home.” She lives vicariously by seeing the younger girls learning tailoring and English as she never went to school. Until four years ago she was illiterate.

“Now I can read and can’t be cheated on prices anymore,” she says. In the morning she reads Prothom Alo, one of the top Bangladeshi daily newspapers. Her next goal is to teach her grandson how to read and write and to better establish Nari Jibon. “I love the project.”

Nari Jibon pays her 1,000 Tk a month, a quarter than what it used to be before December 2008. Rent for her approximately 12 x 12 feet room in the neighborhood costs 1,800 Tk a month. “I have a small house,” she says as she leads me down the narrow passage to her homestead, which she shares with her 25-year-old son who works as a rickshaw puller, his wife Lovely, and three year old son Rapi. Lovely will start a job in the garment factory next month, sowing on buttons.

Outside her house, a row of stoves provides a shared kitchen. Ruma’s flame heats a pot with boiling egg curry. As we sit down on her bed she proudly shows her writing exercises while neighbor women and kids quickly gather at the door, spill into the room, and men peek through the window to eye Ruma’s strange visitor.

A neatly dressed girl in a red and white three-piece with sparkling earrings stands out. Fatima doesn’t know if she is 13 or 14 years but says she also works in a garment factory, motioning to a boy nearby she indicates that she helps produce men’s pants. Every day except Sunday she walks half an hour to start her eleven-hour shift in the factory. Usually she works eleven hours, she says, but today there was not much work and she walked back home by one o’ clock.

As I leave a little girl tries to take my hand, a young man poses to have his picture taken, and Ruma says she’s happy I visited her house.

Learn more and see all of Stine's reporting: http://www.

Friday, July 10, 2009

My first week in Mysore

I arrived in Mysore 9 days ago and have already experienced Indian culture! The traffic is very disorganized, as horns sound all the time and there don't seem to be many enforced rules.The peopl of Mysore seem very friendly and the area seems safe. It's the monsoon season, so there are many rainfalls throughout the day. In Bangalore, horns started honking without a pause at 6 a.m. and people chatted loudly. Every morning, I hear a man singing "tomatoes, tomatoes, tomatoes,..." and some words in Kannada, the local language. Men walk through the neighborhoods every morning, selling fresh fruit and vegetables.

"There are two different Indias in India... one is the one you've seen and the other one is the rural part," Nanjappa, vice president of rural projects, said.I went into the village Begur yesterday and will study the culture of rural India for the next week. Rural India is home to over 70% of the population, according to the International Human Development And Upliftment Academy (IHDUA), the organization for which I intern. After my observations, I will work for two local newspapers. The IHDUA based in Mysore is a non-government organization established in 1991 by Oncologist Dr. B. S. Ajaikumar. The organization works on four main rural projects: rural literacy, women empowerment, economics, health and education, and awareness about health and hygiene. The IHDUA now works with 55 villages.Yesterday, there was a Self-Help Group (SHG) meeting in Begur. These meetings help a group of men or women to ameliorate their businesses and upgrade their skills. I first sat with a group of men who try to work together to strive for economic development. Because the majority of the rural population doesn't speak English, I could not understand most of the conversation. After the second meeting, which was among women, I went into a room with six girls who produced purses. The other women returned to their businesses, which include selling fruits, vegetables, flowers, chicken or sheep fur. Some of the girls knew some words of English and asked me for my name and my parent's name. Two girls used sign language to ask if I had eaten lunch, which in India means about the same as how I was doing.I rode on the back of a motorcycle the "Indian way" (girls sit sideways) and visited some local stands.

On thursday, the first stop was at a small kindergarden and school. The children seemed shy, because they sat quietly on the floor the entire time. The kindergarden was one room with one small desk and one chair. The walls were full of colorful pictures, so that the children could learn the words of different fruits, vegetables, animals, body parts and so on. Before I left, I wrote a few sentences in a guest book and saw that two other Americans have visited this place.

Unlike the kindergarden kids, the school children wore a uniform. I have noticed that most schools in this area require uniforms, often blue- or green-colored.

My driver then took me to see some rural projects of IHDUA. We stopped at several houses in about 8 villages and every person was very welcoming and friendly. Every single household offered me chai tea and some gave me snacks as well.

In one village, I saw a kitchen garden constructed by IHDUA. The purpose is to provide nutrition through vegetables and fruits to the habitants. I also sat in another SHG (Self-Help Group) women's meeting. The women seemed very interested in my culture as well and my driver translated their questions to me. They asked if I was married and if I wanted to stay at the village with them sometime.

The second project I visited a smokeless oven, provided by IHDUA. According to Nanjappa, women used to inhale smoke and get sick while cooking, so the organization constructed one where the smoke goes outside only.

In a different village, I observed the production of silk. There were large wooden wheels on the front porch with hundreds of silk worms weaving. One of the men told me that it takes three days for the worms to construct the material. I refused a chai, but got one anyway. It seems as if nobody takes "no" as an answer here regarding to food or drinks.

Although it was pouring this morning, it fortunately stopped once we got to Begur. I had a different driver today and the motorcyle seemed to be going a lot faster. Because the villages today were a little more distant from Begur, we visited fewer areas. The people at the first house were keeping different food items, such as mangoes and spicy pickles, in different-sized, blue containers. Provided by IHDUA, these items apparently ameliorate their business. At the next village, we visited a woman that was tailoring, such as the girls in Begur.

At the last stop, women were preparing nutritional supplements for malnourished children.

Career First, Marriage Later -- A Visit to Nari Jibon in Dhaka, Bangladesh

Stine Eckert traveled to Bangladesh as a Pulitzer Center Student. Learn more and see all her reporting: http://www.

Girls and women learn sewing, English, and how to use a computer at Nari Jibon Development Foundation -- A visit to a struggling women’s project in Dhaka. Part 1

Rozina and Shompa stand up as if a teacher called on them when I enter the room. After settling that they can sit down they seem to be a bit more relaxed. Shompa has pinned a bright pink piece of cloth underneath the needle of the sewing machine in front of her. She has been learning to sow at Nari Jibon Development Foundation for a month now, working in the small room four times a week for two hours. After she first tailored a fatua, a short-sleeved lose shirt, she’s now on to sow a dress.

“Pink is my favorite color,” says the 20-year old political science bachelor student at National University. It will take her a day to make the whole three-piece, a typical traditional outfit for women in Bangladesh consisting of a dress, long loose pants, and a scarf wrapped around the shoulders. But it saves money and is good practice.

As Shompa, which means dream, becomes more skilled she will be able to tailor a three-piece in three hours, just like expert tailors. After her training is over two to three months, she can buy her own sewing machine and work at home. “I want to start my own tailoring business.“ Shompa says, a source for income at the side for her, even when she reaches her goal to become a teacher in political science.

Twenty-twos girls are currently in the tailoring class at Nari Jibon. As the organization struggles to find donors, according to Project Director Golam Rabbany Sujan, Nari Jibon, which means women’s life, had to raise the admission for the course.

Since December 2008 every girl pays 500 Tk or $7.50 to participate up from just 300 Tk ($4.50). In 2007 the girls only paid 100 Tk ($1.50). Fees were low as Nari Jibon started out to especially help poor, underprivileged women. But with a drop in donations it has opened up for everyone who can pay.

To pay her admission, 15-year old Nipu Akhtar works part time in an office, where she helps with accounting and binds books. With her monthly-earned 1,000 to 1,500 Tk ($15 to $20) she can almost pay for her three courses; her parents pay the rest.

Nipu not only learns tailoring but also English for 500 Tk ($7.50) each, and how to use Microsoft Office and create graphic designs, for another 1000 Tk ($15). With her new skills she wants to later open her own boutique to sell dresses.

She says if a woman is not educated, the family wants the daughter to marry to decrease family expenses. “I want independence,” Nipu says. “I will never marry. Only if a nice boy comes and then only after twenty years.”

Opposite to her sits Shadia Islam, 18 years, who already won a little independence by simply coming to Nari Jibon. She says her father was not willing to pay the fees. Besides, he didn’t like the idea she would be working outside her home, she says. But her mom supported Shadia: “My mom pursued my dad and changed his mind, she said to him ‘ Better do it, there’s no gain but no loss either.’” She has one more year in high school and wouldn’t mind marrying after a while, she says. “But I want my parents to find me a husband.”

Similarly Tasnuva Swarena, 22, doesn’t rule out marriage. But she also wants to have a job hoping that the computer class will help her to later find a government or bank position. She will graduate from Dhaka University with a Bachelor in anthropology in three months. But even when she finishes her master in another year, she says “there’s little chance I find a job in anthropology.”

Photo: "Pink is my favorite color," says 20-year old political science student Shompa who later wants to open up a tailoring business at home.

Learn more and see all of Stine's reporting: http://www.

Sunday, June 21, 2009

A Protester Speaks Out From Tehran

By Taylor Mirfendereski

The following is the transcript from my June 20 (June 21 in Iran) interview with a young Iranian protester in Tehran, Iran. She has taken a big risk to speak with me. To protect her safety, I will refer to her as Parisa.

I first communicated with her by phone, but because many phones in Iran are tapped, she preferred to communicate through the Internet. I have corrected the grammar and English of her responses for clarity, but have not altered the content.

Photos in this entry are courtesy of The Boston Globe.

TAYLOR: Have you gone to any protests?

PARISA: Yes, I go to all of them!

TAYLOR: What are your reactions to the protests and riots?

PARISA: I participate in all of them because I am sure that there is a big [election] fraud. In fact, the reason for the increase in voter participation was that [the Iranian citizens] see the lies that Ahmadinejad tells for themselves. Everyone said, “It doesn’t matter who will be president. We will vote to not let Ahmadinejad get elected [again].” This election was the first time that we ever had this large of a voter turnout (40 million).

Until now, I believed that these protests were good because it shows our population. Imagine, they say Mousavi won about two million votes in Tehran and on June 15, our biggest rally, there were three million of us who attended. For example, everyone in my family voted for Mousavi, but I was the only of us who attended the rally. Therefore, you should multiply the population.

Another reason that I was in favor of rallies was because the government’s threats of arrest, violence, and even killing people, no longer has an effect on the will of people.

Imagine, on June 15—from morning until the last minutes of the rally– every 15 minutes in all news, they said, “There is no permission for a rally. If you go, we will behave violently. There will be serious sanction against people who attend this rally.” Many of my friends were really frightened by this because the day before, the Basij (militia) started their violent actions. We saw their brutality, but we went.

Interestingly, they asked taxis and busses to not take people to Enghelab Square (where the rally took place), but we went and we showed them how many of us there were and how brave we are. It had a very good effect.

TAYLOR: If you look outside of your window, what do you see? Are there people on the streets protesting?

PARISA: In fact, no! Only at 10:00 pm. At this time, everyone chants “Allah Akhbar” (God is great). But it’s really stupid because after two days of saying “Allah Akhbar,” they [the government] said that the Iranians chant “Allah Akhbar” for Ahmadinejad. After that day, we changed our chants to “Allah Akhbar” and “Ya Hossein, Mir Hossein” to show that we are protesters of Ahmadinejad. (NOTE: Mir Hossein, as said in the chant, refers to Ahmadinejad’s opposition leader.)

TAYLOR: Can you leave your house? Is it safe?

PARISA: In the morning, yes, we can go and it is safe. During the first days after the election, it was even unsafe in the morning. People were gathered close to their homes and offices and the police hit every body. An interesting issue that I want you to pay attention to is that in the middle of election day—before it was finished—they [the government] said, “Tomorrow, any gatherings are forbidden!” I wonder how they knew that people would gather the day after the election? At that time, the election wasn’t even finished. We were still voting! So, it shows that there is definite election fraud because they were sure that after they announced the winner there would be protests.

TAYLOR: Are you scared? Why or why not?

PARISA: When I saw the basij, I was so scared that I couldn’t breathe! Imagine, there were 30 motorcycles, two people on each, without uniform—like normal people, with batons. They had beards and their faces were very aggressive. You know, I am a lawyer. I know the dangers of letting normal people interfere with governmental issue. The problem is that they don’t work for money like all the other police. The basij work for their beliefs. So they think they will go to heaven by killing those who protest against Khameneyi (Supreme Leader of Iran). After Khameneyi spoke during Friday prayer, I got so scared. But I don’t have any fear of being killed.

TAYLOR: Have your friends gone to any protests?

PARISA: Many of my friends went, but some didn’t go because they were scared.

TAYLOR: Has anyone you know been injured or killed? Please explain what happened to them.

PARISA: One of my family members had his head broken. He was hit by a baton.

TAYLOR: How has the atmosphere in Iran changed from before the election to now? What is the atmosphere like now? Are people more open to speaking out against the government?

PARISA: It is very amazing because all of the people have become more brave. You see many artists, soccer players, and lawyers protesting in so many ways. When I was at the rallies, I noticed that people were kinder than before—they help each other and I feel there is a big change. We don’t have any leader in our rallies, but everyone respects the rule of being silent. For Iranians, who usually don’t obey the rules, it is very interesting. I think that the capacity of bearing injustice and watching the lies of government is full. That is the reason that we have all become brave.

TAYLOR: Did you expect it to change like this? Are you surprised?

PARISA: One week before the election, there were signs of something strange. You know, we had televised debates between the candidates, and in all of them we saw that Ahmadinejad said too many lies. He accused the candidates of so many crimes. The day after, the formal institutes who were responsible for the information that Ahmadinejad said, sent a formal letter to TV channels and said that Ahmadinejad tell lies. The TV stations didn’t read their mail and said that they would read it after the election (although they still haven’t read it) and so we see there is a power who wants to show Ahmadinejad as a good person and show the opposition as liar. The day that all of this happened, I thought, “If this power wants to ignore people’s vote because of the lies that Ahmadinejad told in front of 70 million people who have brains and can think, there will be tension in society.” However, I didn’t know that Mousavi was this brave.

TAYLOR: Who is protesting? What are the demographics?

PARISA: It’s very interesting. All ages—even very old people and religious people. You can see all kinds of people. If you have access to the video of Friday prayer, compare the people who were there with the pictures of the protesters. There is a big difference. But I have to say that most of the protestors are young and most of them are educated.

TAYLOR: Can you drive your cars on the streets or are they blocked with people?

PARISA: Rallies are at a specific time and place so cars cannot move just at that time and that place.

TAYLOR: How have people organized their protests if cell phones are shut down?

PARISA: They use their landline phones. Some people who can pass filters use their Internet and email to find out. Our mobile phones sometimes work and sometimes don’t work. But when we go to rallies, they are completely shut down. The SMS (text message) system has been off since the day of the election. All of Mousavi’s websites are blocked. He has tried to make other sites, but the speed of our Internet is very slow. During the rallies, people share the next day’s schedule with each other. Imagine, without having tools for communication, the Iranian people are this strong! So if we had communication access, then we could be much more!

TAYLOR: Can you access information? How? Which information can you access?

PARISA: With difficulty. Our TV has only government-owned and operated channels. It has become the god of lies. It makes us crazy and recently, I haven’t watched it because it makes me crazy. We have to try so hard to find true information and so there are not too many people who have the time or tools to find it. So I have to say no. We don’t have access.

TAYLOR: Can you still go to work this week? Why or why not?

PARISA: I could! But I didn’t. I was so tired of rallies and not sleeping. I didn’t sleep because I have been trying to find information on Internet.

TAYLOR: What outcome will come from this situation? What do you foresee for Iran's future?

PARISA: This election marked the start of change. I don’t know when there will be change, but I am sure the start day is today.

TAYLOR: What is the overall energy in Tehran right now— fear, excitement, hope, etc.?

PARISA: It goes up and down. The first day, we were so upset. We didn’t see any hope. After the June 15 rally, we got happy, but again after Khameneyi spoke at Friday prayer, we became so sad and scared.

TAYLOR: Is this another revolution? Do you believe that a revolution is needed?

PARISA: No. We just want to have another election with a supervisor who is not in favor of anybody who is running. But after Khameneyi’s speech in Friday prayer, I don’t know what will happen.

TAYLOR: Who did you vote for in the election? Who do you think won? Do you think they will do the election over? Why or why not?

PARISA: I voted for Mousavi. I thought he would win and I am sure he is the real winner. Their [the government’s] behavior shows that they will not have another election because they want Ahmadinejad to be the president, even with the price of killing their people.

TAYLOR: Describe the most memorable thing that you have seen since the protests and riots began on election day?

PARISA: The amount of people who came to the rally on June 15 (3 million). Although, the best thing was that they said they would attack us.

Yesterday, June 20, the amount of basij and police and their brutality was the worst thing I’ve seen. I cried the whole time. They hit everyone. Old, young, girls, boys. They didn’t let us gather. You know, when the population is spread, we are vulnerable. Yesterday they tried to spread people. They used everything. I heard the sound of guns. They were very scary. There were too many basij. I think they came from all over the country.

TAYLOR: How is the older generation reacting to everything? Upset, excited, scared?

PARISA: They are active in protesting and they think like the younger generation.

TAYLOR: Have you met anyone who is upset with the situation?

PARISA: Every one is upset!

TAYLOR: Why is it safer to communicate online than on the phone?

PARISA: The government controls the phones and records the conversations. They try to say America and England are leading the protesters. For example, last night in Iran, the Iranian news stations said that there is evidence that proves England had influence in this situation. Their evidence was the voice of a woman who was talking on the phone and asked her friend to burn the cars, banks, and say death to Khameneyi.

TAYLOR: Has the city of Tehran shut down? Are the malls and restaurants open?

PARISA: In the morning, they are open. But during the evenings, the places close to the rallies are closed.

Topics: Iran, Iran Presidential Election