By: Hiram Foster

Edited by: Alex Stuckey

In September 2009, the Indian government issued its first Unique Identification Number (UID), a randomly generated twelve-digit number that will provide a universal identity to every Indian resident.

The UID program is similar to the US Social Security Number. However, what makes the UID unique is the implementation of biometric data used to associate an identification number with a specific individual.

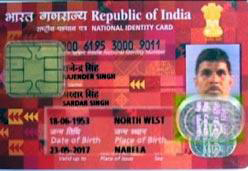

Citizens are issued an Aadhaar card, literally translated to base or foundation, that contains their UID information along with all of their biometric data.

In order to obtain an Aadhaar card, citizens visit a registration facility where all ten fingerprints are scanned. A digitized pattern of the iris of the eye is then created, along with a photograph of the applicant. This ensures that there is only one number for each individual, according to the UID website.

The information collected will be entered into a government database, slated to become the largest biometric database in the world at 1.2 billion registrants, once the government funded initiative is complete. The initiative was created in part because of the 2008 terrorist attacks in Mumbai.

“There’s supposed to be a chip on the card that carries all of your information, there’s a lot of details about you on that chip that can be read into a computer,” said Aaboo Varghese, a spokesman for Oasis India.

Varghese works at Oasis India’s national office in Mumbai. This Christian non-profit organization works to end human trafficking by taking women out of brothels, educating them with life skills and helping them integrate into mainstream society.

“Many of the women we work with do not have any kind of documented identity,” he said. “One of the main things we try to do is get them a PAN card so they can open a bank account.”

The PAN card is just one form of identification used specifically for filing tax returns and holding bank accounts, Varghese said.

The issue of identification has plagued India since its population began overwhelming the country’s infrastructure, he said.

Not only does the phenomena of slums and shantytowns demonstrate this but also the high occurrence of duplicate and “ghost” identities.

Prior to the program, there was no unique identifier for Indian citizens. Citizens may possess a PAN cad, a ration card, a passport, a voter identity card and an employment card, among others.

Many of these forms of identification function to provide services or rights to the underprivileged, but fall short in the realm of security and anti-counterfeiting measures.

The UID program will make all of these forms of identification unnecessary by linking all government forms, services, and bank accounts to this one number.

A large portion of India’s population falls below the international poverty line, estimated at 41 percent by the World Bank. Many of these people have no proof of identity or even date of birth.

In fact, it is not uncommon for them to be unaware of their exact age. Many forms of identification also require applicants to provide a permanent address, a disqualifier for many.

“Often, we must ask a government office to help provide some kind of resident address so that the women can even apply for a PAN card,” Varghese said.

These obstacles have proven frustrating to the Oasis workers as they struggle to help women entrapped in sexual slavery, he added.

The UID program allows those without this kind of information to have an official identity recognized by the government.

Although it does not provide “rights, benefits, or entitlements,” according to UIDAI, it is hoped that the “UID method of authentication will improve service delivery for the poor.”

If the UID proves true in eliminating loopholes, it will be a good system to give an identity to everyone, Varghese said.

“It could prove to be helpful because it cannot be duplicated easily, but I’m not in a position to say how well it will work with the poor,” he added.

None of the women that the organization has worked with have received UIDs, said Hazel Solomon, who also works at Oasis India.

There have been mixed reactions to the program, Varghese said.

“Everyone thinks it’s a means of keeping a tab on you and that it won’t really solve the rich-poor problem,” he added.

He added that he was concerned about the program because it took privacy away from people.

“It makes it easier for the government to track people in the wake of terrorism,” he said. “It could be misused for controlling peoples lives and invading privacy.”

Despite the concerns of Varghese and many others, Amar Bakleekar, an official from the Nandurbar district, said a lot of people will benefit from the program. This district was where the first Aadhaar card was issued.

“We can use the UID in various programs. For example, it stops people from using fake identities who want to get food from counterfeit ration cards,” Bakleekar said. “The UID makes it impossible for you to enter wrong numbers into the system.”

Well over one million unique identification numbers have been issued. The program is on its way to bypassing the current largest biometrics database, held by the United States with 1.2 million.

In December 2010, MasterCard Worldwide joined the program, announcing that it had developed a “direct interface with UIDAI to preform UID biometric authentication of payment transactions.”

UID holders can now use their Aadhaar cards to make electronic transactions.

Some are concerned about the idea of an exhaustive database that contains the information of every official document, financial account and biometric data of every citizen in one, centralized location.

“I think the benefits of the program outweigh the risks of privacy, but I’m still reminded of what the Bible says about revelation and the Anti-Christ, so I guess we will just have to wait and see,” Varghese said of such a database.

No comments:

Post a Comment